To surf Africa’s biggest wave, which rises to 50ft and crashes down on waters filled with great white sharks, you first need to take a boat out into the clashing currents of Cape Town’s Hout Bay. Then you jump into the maelstrom, paddle like crazy towards the deafening roar of breakwater, and suddenly it’s right there under your bracing, twitching legs: Dungeons, as this terrifying colossus is called, propelling you towards the shore. “It blew our minds,” says Cass Collier, one of the first surfers to trace a line down this notorious wave’s surging facade. “We felt like babies.”

It was the late 1990s and Collier’s parents, although South African-born, were of Indian heritage, which meant the apartheid regime classified him as “coloured”. But in brutal heavy surf, he says, all racial differences ceased to matter. “You’ve got to have a clear mind and a clear conscience – and know that your fellow surfer in the water with you is your brother. If anything happens, he’s the one who’s going to help you.”

Collier, who went on to become the first non-Hawaiian surfer of colour to hold a world title, is one of the stars of Afrosurf, a resplendent 300-page book charting Africa’s overlooked surf culture. Starting with South Africa – the continent’s waveriding mecca – Afrosurf asks a host of characters from a dozen countries what being an African surfer means today. Posing in boxing gloves on his board for the book’s cover, Ghana’s Sidiq Banda speaks for everyone when he describes surfing’s otherworldly appeal: “I used to have wave dreams … it’s like a first-love thing. It’s like light-blue walls, and you’re flying. That’s when you get hooked, when you just need to keep going back because you’re constantly dreaming about waves.”

The book takes a whirlwind tour of the African coastline, from the empty breaks of the Horn of Africa, to Morocco – pummelled by waves in winter – and the Almadies peninsula in Senegal, a current buzz destination with one of the largest swell windows in the world. Then it swings round Africa’s “bulge” to the sub-Saharan countries – Ivory Coast, Nigeria, Ghana – that have big wave-riding potential if the right Roaring Forties storms dispatch a swell their way. At every pitstop, Afrosurf digs into the culture – music, art, folklore, food, the chances of meeting a hippopotamus where the waves break – that surrounds an activity that’s as much lifestyle as sport.

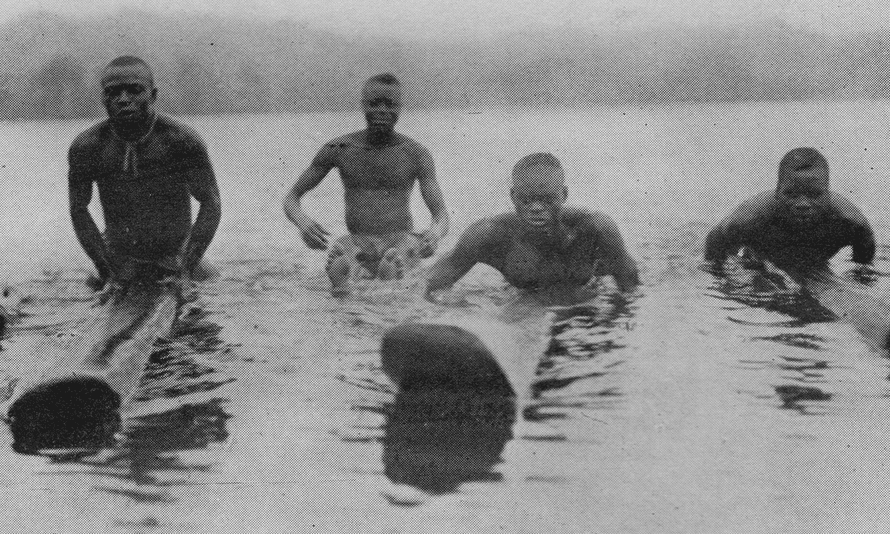

Perhaps most crucially, the book, which is stuffed with evocative, spray-lashed photos, upends the received narrative that surfing originated solely in Hawaii and was later adopted by white Americans and Europeans, who spread it around the globe. According to Afrosurf’s introduction, in the 1640s Michael Hemmersam, a German goldsmith working for the Dutch West India Company, watched children in what is now Ghana ride waves on wooden boards. He believed, probably erroneously, that this was how they learned to swim – but he inadvertently created the first written account of African surfing.

Three centuries later, American director Bruce Brown landed in Africa to film segments of the classic 1966 surf documentary The Endless Summer in Senegal, Ghana and Nigeria. His attitude towards what he viewed as virgin territory hadn’t moved on much from colonial times: Brown boasted of discovering “surf that had never been ridden before” – even though, in his own footage, you can see children of Ga ethnicity clearly using traditional paddleboards.

Kevin Dawson, the former competitive surfer and now University of California academic who wrote the Afrosurf intro, says Brown’s attitude typifies the “intentional erasure” of this part of African culture. “Seeing the boards in Ghana doesn’t fit into his simple narrative,” he says, “so he just swept it under the rug.”

It’s beyond question now that the sport belongs to a much wider group of people than the blond-haired archetype that became shorthand for “surfer”, from the Beach Boys to that classic cinematic stoner Jeff Spicoli. And Collier was one of the first to make a breakthrough. He grew up in the tough Cape Flats area and was pushed by his father to surf at the then whites-only Muizenberg beach as an act of political defiance.

“I weathered through it,” he says, “but a lot of my crew didn’t want to carry on surfing because of that confrontational vibe.” He advanced quickly, trailblazing intimidating breaks like Dungeons, as well as discovering and naming a left-breaking wave – Madiba’s – near Robben Island, where Nelson Mandela was incarcerated. But he was still forbidden from surfing in South Africa’s national events.

The authorities finally relented, but Collier had already decided to compete abroad. His mastery eventually won out. With fellow Rastafarian surfer Ian Armstrong, Collier won the 1999 Big Wave World Championship at thrillingly named Killers, a wild spot 20km off Mexico’s Pacific coast.

Encouraged and supported by his family, Collier was better set up for success than the average black South African. Even today, although there is no official segregation, watersports are not readily accessible for people in townships, says Chemica Blouw, a coach with the Waves for Change “surf therapy” programme. “Growing up,” she says, “the beach was a once-in-a-while visit or for a special holiday. We’d see surfers with blond hair, blue eyes and white skin. It was intriguing to us, but we never thought we’d have the opportunity to pursue it. I remember telling my grandparents when I was in high school that I was going to start surfing, and my grandfather laughed and said, ‘Oh, is jy nou wit?’ (‘Oh, are you white now?’)”

The growing prominence of African surfing, and within that the growing involvement of black wave-riders, could finally break down lingering pockets of prejudice. Afrosurf is testimony to the growing diversity on African beaches – and this includes women. We hear the story of Berber surfer Maryam, whose determination to surf her home beach of Tamraght in Morocco earned her a new name: “They called me Mohammed. Because I was surfing like a boy. I was really strong, I didn’t let anyone put me down.”

But competitive surfing still needs to catch up, says Collier. He was disappointed to see no surfers of colour on a recent visit to Jeffreys Bay, the Eastern Cape town that hosts the World Surf League. Asking people if localism – the surfing practice of aggressively discouraging outsiders at a break – was responsible, Collier was told no. He’s still trying to figure out what is keeping black surfers away: “They’re afraid of something, I don’t know what it is. There’s still this taste in everyone’s mouths of the exclusivity of surfing. Some kids are still quite scared to challenge the hierarchy.”

Holy waters: the spiritual journey of African migrants – in pictures

Read more

Godspower Pekipuma, one of what he estimates to be 20 Nigerian surfers, has this to say of his homeland: “Most Nigerians don’t know how to swim. They say they are taking risks – and Mami Wata, the goddess of the sea, is going to drown them. They don’t see the value and the therapy of it.” Kevin Dawson has encountered such fears too, but sees a potentially fertile side to them: “Though most people in coastal Africa are Christian, they do still maintain traditional beliefs. And so there does seem to be this blending of western surfing with traditional African beliefs and practices that’ll be really interesting to watch.”

That fusion could give the 21st-century African surfer a unique identity, a sense of connection to the water comparable to Hawaii’s famous spirit of aloha. But such talk of deities is simply putting different faces and interpretations on a sensation that is universal and uplifting. As Collier puts it: “If someone goes in the ocean, and feels happy and free, then they won’t be able to come out and live as a slave.”